The US Treasury yesterday designated what it described as “Iranian national and liquified petroleum gas (LPG) magnate” named Seyed Asadoollah Emamjomeh, along with his network of companies that facilitates the shipment of hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of Iranian LPG and crude oil to foreign markets.

According to OFAC, Emamjomeh owned or controlled at least nine entities involved in Iranian LPG shipments, including one company with a monopoly on the National Iranian Gas Company’s LPG deliveries.

For more than a decade, Iran-based Seyed Asadoollah Emamjomeh (Emamjomeh) and his son, United Arab Emirates (UAE)-based British and Iranian national Meisam Emamjomeh (Meisam), have owned and operated an LPG sales, transportation, and delivery network using multiple Iran and UAE-based companies. Emamjomeh and his UAE-based company, Caspian Petrochemical FZE (Caspian Petrochemical) are part of a network that has exported thousands of shipments of LPG from Iran to Pakistan and have conducted tens of millions of dollars in business on behalf of Persian Gulf Petrochemical Industry Commercial Co. (PGPICC).

OFAC noted that until recently, the elder Emamjomeh was the owner of UAE-based Pearl Petrochemical FZE, before passing ownership to his son in October 2024. According to OFAC, Pearl is the beneficial owner of the vessel TINOS I (IMO 9969821), a Very Large Gas Carrier that attempted to load LPG from the United States in June 2024 for sale to China. Meisam acts as director and chief executive officer (CEO) of UK-based Worldwide LPG Limited, while also serving on the board of directors of many of Emamjomeh’s Iran-based companies.

Why is this significant?

This is not the first time Emamjomeh and his network are in focus. Lloyd’s List in November 2023 reported the results of their investigation into the Georgian (country, not US state) owner of a restaurant in South London who appeared to be acting as a front for a fleet of aging gas tankers used to ship hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of sanctioned propane and butane from Iran.

The Lloyd’s list investigation involved a particularly old tanker, the Panama-flagged White Purl (IMO: 7230666). A fire broke out on the 51-year-old vessel while it was anchored off the port of Assaluyeh in the southern province of Bushehr, Iran. Only one problem: its Automatic Identification System (AIS) signal showed it to have been anchored in a completely different location - hundreds of miles to the southeast, near the island of Abu Musa.

🔻Red flag: AIS spoofing is commonly used by vessels violating sanctions.

After a bit of research, Lloyd’s list traced the aged tanker’s tangled ownership to Georgian and UK national Tamila Jmukhadze—part-owner of the Kartuli restaurant in the East Dulwich neighborhood in London.

🔻Red flag: Tangled ownership and control structures.

There were some seriously complex ownership networks involved in the White Purl, which was scrapped after the fire in 2023. Jmukhadze was president of Panama-based Taboga Maritime & Transport SA, the registered owner of White Purl since October 2021, according to Lloyd’s.

According to Lloyd’s List’s analysis of sale and purchase documents, public access databases and a cache of leaked documents posted on the WikiIran website, Jmukhadze is also linked to 13 other gas carriers involved in shipping Iranian LPG via her control of numerous Panamanian companies.

And the other vessels linked to Jmukhadze have also been found engaging in AIS spoofing and other deceptive shipping practices. Jmukhadze is not sanctioned by the United States, the EU, or the UK.

Shared tactics.

OFAC recently released an update to a 2019 advisory, providing additional guidance for the global shipping and maritime industry to help stakeholders identify sanctions evasion related to the shipment of Iranian-origin petroleum, petroleum products, or petrochemical products.

Given Iran’s reliance on energy shipments that help it fund its destabilizing activities, terrorist proxy groups, and weapons of proliferation, the country continues to develop sanctions evasion methodologies to facilitate its continued shipments of crude oil and other energy products.

The “shadow fleet” of tankers that transports Iranian oil generally is old and shabby, like the White Purl—poorly maintained vessels and operating outside of standard maritime regulations. These types of vessels also transport Iranian LPG, primarily to China, according to OFAC. The updated advisory warns of deceptive tactics such as ship-to-ship transfers, fake cargo and vessel documents, and obscure oil-brokering networks, in addition to the red flags I highlighted above in relation to the White Purl.

But Iran is not the only country that uses these same tactics.

The RAND Corporation in 2021 issued an 82-page report on North Korean sanctions evasion. In addition to theft of currency, especially virtual assets, the DPRK regime also engages in covert transportation (smuggling) of goods that obfuscates the Kim regime’s involvement.

North Korea has a low number of international road and rail connections, RAND noted. This makes air and sea the main methods of transport to move goods in and out of the country.

Maritime transport plays by far the dominant role, particularly for weapon shipments. Both India and Spain, for example, have intercepted North Korean cargo vessels that were carrying missiles concealed beneath regular civilian cargo. North Korea uses barges and tankers for clandestine at-sea ship-to-ship transfers of coal and oil in violation of UN sanctions on their export and import.

Aside from ship-to-ship transfers, North Korea also uses front companies and other complex ownership structures, changes in vessel names and flags, and physical obscurement of the vessel names and IMO numbers, as well as fraudulent declarations of cargo, to evade sanctions.

Russia engages in similar evasion tactics as its friends in Iran and North Korea.

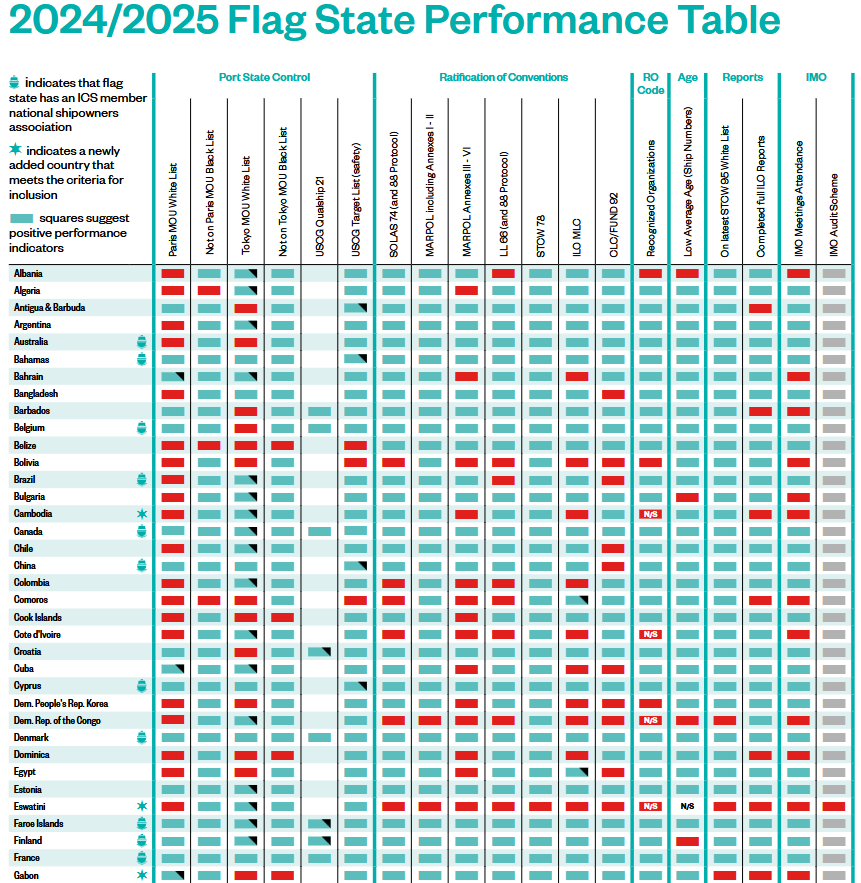

Flag-hopping—or switching flags and registrations to jurisdictions with lax controls—is a common sanctions evasion methodology. The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) this year added four new flag states—Cambodia, Eswatini, Gabon, and Guinea-Bissau—to its monitoring system, indicating concerns about entities and vessels with potential sanctions links, using these jurisdictions to register their sanctions fleets.

Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland) isn’t even a signatory to the UN’s international maritime conventions, but apparently it’s giving out flags to random vessels like lollipops. That’s why the ICS issues its Flag State Performance Table which, for the past 20 years, has been updated annually using objective externally published data.

Notice the amount of red flags Eswatini is sporting. This should act as a warning for any stakeholder in the maritime industry.

Ukraine recently flagged three Russian “shadow fleet” ships sporting Eswatini flags. Numerous others include Panama, St. Kitts and Nevis, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and others. The list is long and distinguished. You can find it here.

OFAC in 2020 also issued a tri-seal advisory for the maritime, energy, and metals sectors, as well as related stakeholders, highlighting the same red flags I noted above, with a focus on Iran, North Korea, and Syria. And these are red flags that can and do apply to Russia, so make sure you’re reading all guidance. Illicit actors share methodologies.

In a more recent advisory on Russian evasion of the $60-per-barrel price cap on Russian oil, the Price Cap Coalition (comprising the G7, the EU, Australia, and New Zealand) last fall issued an updated advisory for industry stakeholders looking to detect and deter Russian evasion. Again, these strategies closely resemble those of other illicit actors, including AIS manipulation, ship-to-ship transfers that involve shutting off tracking and many times offloading cargo at nighttime, causing environmental risk, and other evasion methodologies.

Inflation of ancillary shipping costs is a common Russian technique to evade the price cap, according to the advisory. Ancillary costs can include freight, customs, and insurance, and bundling them with the payments for oil can be used to conceal the fact that Russian oil was purchased above the price cap.

Shipping, freight, customs, and insurance costs are not included in the price caps and must be invoiced separately and at commercially reasonable rates. Industry stakeholders involved in the Russian oil trade should require an itemized breakdown of all known costs negotiated at the start of the trade transaction (e.g., port dues, freight, and insurance costs). As of early 2024, coalition service providers are required to request such information in certain circumstances, including, but not limited to, requests from relevant authorities. This entails industry stakeholders updating contractual terms and conditions with sellers or counterparts or adjusting invoicing models to show the price of the oil until the port of loading and the price for transportation and other services separately.

Mitigation strategies.

Keeping track of regulator guidance and applying the recommendations contained therein to compliance programs is critical. Training compliance officers to be aware of evolving evasion methodologies will help keep compliance personnel current and aware.

Sanctions screening is no longer enough, since many of the illicit actors, such as the ones mentioned above, use front companies and tangled ownership and control structures to obscure the involvement of sanctioned jurisdictions or entities in transactions.

Monitoring tanker sales and tracking vessel histories may seem onerous at first, but doing so can help organizations avoid involvement with blocked property, and checking previous names and registrations against sanctions lists is key. If a vessel recently changed its flag and registration to a jurisdiction with with lax controls, it’s an indicator of possible illicit activities.

Reporting vessels that trigger concerns to regulators can help ensure that the organization remains on the right side of the law. Is a vessel involved in suspicious activity, such as turning off AIS or taking circuitous routes to its destination? That should trigger concerns and closer scrutiny.

And then, there’s the due diligence. If a vessel has undergone numerous administrative changes such as re-flagging, name and ownership changes, is old and has a history of incidents or deficiencies, enhanced due diligence may be in order. The use of intermediary companies (e.g., management companies, traders, brokerages, etc.) that conceal their beneficial ownership or otherwise engage in unusually opaque practices should also trigger closer scrutiny. Such companies—especially if they’re located lose to a highly sanctioned or embargoed jurisdiction—may be more likely to engage in deceptive practices and expose counterparties to heightened risks.

Good luck out there! It’s a challenging environment.