The Wall Street Journal had an interesting story this morning about North Korean IT workers exploiting desperate Americans to gain access to US company systems and money. I knew that North Korea has been using all sorts of fraud and other duplicity to impersonate US citizens, gain remote employment with US companies, steal intelligence, and access hard currency.

Reuters reported in 2023 that North Korean IT workers were using fake names, fraudulent LinkedIn profiles, counterfeit work papers, and mock interview scripts, to get hired by western tech companies. These efforts have accelerated during the past several years and have earned millions to help finance the DPRK’s weapons systems.

Media reporting in April described how a cybersecurity expert posed as a US IT worker to discover more about the North Korean scheme that has impacted hundreds of Fortune 500 companies.

First, Aidan Raney sent a message to a Fiverr profile that he learned was being manned 24/7 by North Korean engineers looking to recruit US accomplices. He just asked how he could get involved.

North Korean handlers then contacted him, all of them posing as someone named “Ben,” apparently not even realizing that Raney knew he was speaking to several different people.

Raney asked his handlers a bunch of questions about how the scheme worked.

The plan was to use remote-access tools on Webex to evade detection, Raney told Fortune. From there, Raney learned he would be required to send 70% of any salary he earned in a potential job to the Bens using crypto, PayPal, or Payoneer, while they would handle creating a doctored LinkedIn profile for him as well as job applications.

Raney would have to show up to video meetings, morning standups, and other calls, while the “Bens” would take care of all the actual work in order to create the impression that a real, US-based person was doing the job. They created his LinkedIn profile, developed a persona that was “well-steeped in geographic information system development, and wrote on his fake bio that he had successfully developed ambulance software to track the location of emergency vehicles.”

The sophisticated scheme aimed to create a fake identity that would pass background checks and closely resemble Raney’s real profile to avoid detection.

The scam has been around for a few years now—since at least 2018—but it gets more sophisticated and complex as novel methodologies are discovered and publicized as a warning to companies. Covid 19 and the advent of remote work created an even more target-rich environment for sanctions-crippled North Korea.

In response to severe economic sanctions, DPRK leaders developed organized crime rings to gather intelligence to use in crypto heists and malware operations in addition to deploying thousands of trained software developers to China and Russia to get legitimate jobs at hundreds of Fortune 500 companies, according to the Department of Justice.

The IT workers are ordered to remit the bulk of their salaries back to North Korea. The UN reported lower-paid workers involved in the scheme are allowed to keep 10% of their salaries, while higher-paid employees keep 30%. The UN estimated the workers generate about $250 million to $600 million from their salaries per year. The money is used to fund North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missile programs, according to the Department of Justice, FBI, and State Department.

North Koreans have developed these schemes to use AI, social engineering, and publicly available information to impersonate US workers. The Wall Street Journal last year reported that North Korean workers have been hired for possibly thousands of low-level IT jobs and other roles in recent years, using stolen identities of foreigners to evade sanctions and gain access to US companies’ IT systems.

Firms hire these remote workers, who use generative AI and other tools to portray themselves as qualified personnel, and then they do everything from deploying malware to stealing intellectual property to generate revenues for the North Korean regime to hijacking the identities of Americans for nefarious purposes.

The laptop farms and other deceptions.

North Korea often uses laptop farms run by middlemen in the United States to install remote desktop software that allows individuals in the DPRK to log in to company servers from overseas while creating the impression that they are located in the United States.

A woman named Christina Chapman, who was hoping to transition careers from massage therapist to web developer, in 2020 received a LinkedIn message from someone in North Korea and began working with the DPRK by October of that year. Her responsibilities to the regime grew steadily. She helped create fraudulent W-2 tax forms or other verification documents when the North Koreans got hired. She would help them fill out their immigration paperwork to help them establish their eligibility to work in the United States. The North Korean IT workers had their company laptops sent to her address, where she would unpack them and install remote access software that would allow the North Koreans to log onto the company systems.

“She made sure connections ran smoothly and helped troubleshoot any issues. Sticky notes on the computers identified the company and the worker they were supposed to belong to,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

Americans desperate for income and job security may perform any number of services for the North Korean regime. Beyond setting up these laptop farms and running software on them to allow the North Korean workers to pretend to be located in the United States, the DPRK regime will hire US individuals to simply provide a mailing address to receive packages or paychecks.

These US enablers can also provide their own identification to the North Korean IT workers or pass “liveness checks”—pretending to be the actual employee every time the employer needs them to turn a camera on for a meeting or a call.

Recognize the signs - forgery and fraud.

The Treasury Department, the State Department, and the FBI in 2022 issued guidance for firms and financial institutions to recognize and mitigate the risks posed by DPRK remote IT workers who work to obtain employment while posing as non-North Korean nationals. The advisory highlighted some of the methodologies North Korea uses to implant its workers in global IT sectors as significant sources of revenue.

Recognizing the risks in specific jobs is key. Jobs building mobile and web-based apps are common among North Koreans looking to gain access to specific systems. Building virtual currency exchange platforms and digital coins, providing general IT support, running mobile games and online gambling platforms, as well as dating apps is common as well. These workers have also been known to work on AI-related apps, develop hardware, software, and virtual and augmented reality programs, build facial and biometric recognition software, and be involved in database development and management.

Much like recognizing higher risk in certain sectors when it comes to trade controls is vital, it’s also critical to understand the risks inherent in these particular jobs.

The IT workers are unlikely to be involved in malicious cyber activities themselves, according to the advisory, but they could be sharing access to virtual infrastructure, facilitating the sales of data stolen by DPRK cyber actors, or assisting with money-laundering and virtual currency transfers. So firms and financial institutions should watch for the use of VPNs and proxy servers, closely examine the profiles of individuals that may be used as proxies, and monitor the use of single, dedicated devices for each of their accounts—especially for banking services—to evade detection by fraud prevention, sanctions compliance, and AML safeguards.

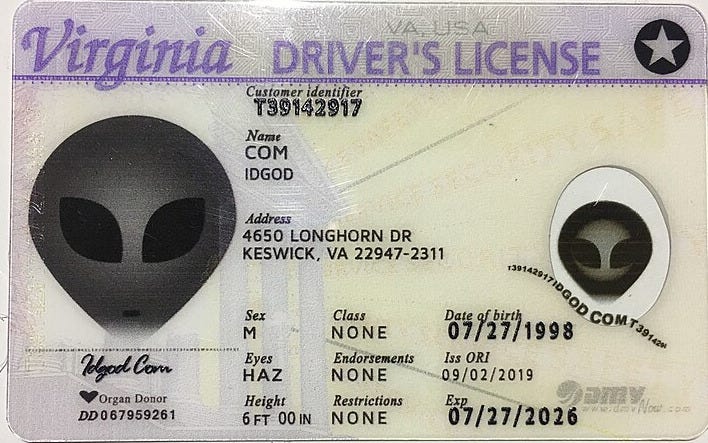

Because North Korean IT workers often get their hands on forged documents, such as driver’s licenses, social security cards, passports, and ID cards and can falsify school records, work visas, and bank statements, look for subtle signs of forgery, such as typos, mismatched fonts, or unusual spacing. Run ID photos through reverse image searches, and know what real national identity documents look like and what fonts and formatting they use.

Although some identities are stolen, as I mentioned earlier, they can also use US facilitators to gain identity documents. Ergo, it’s important to note any differences in ID photos between the documents provided and the “real” individual.

Using fraud detection software to find signs of image fraud is smart. Sophisticated algorithms can compare the original image to a database of known images to find discrepancies, according to Ocrolus - a company that helps financial institutions manage risk by automating document analysis. The more sophisticated the fraud techniques become, the more useful these ever-developing tools will be.

Remember, just because the online profile is detailed and contains work experience of real people at real companies, doesn’t mean the profile is genuine.

DPRK IT workers may also populate their online developer profiles’ employment sections with the names of small or mid-sized Western companies so that the DPRK IT workers appear to be reputable Americans or Europeans when bidding on projects. They may use the names of actual employees and email addresses that appear similar to the Western company’s legitimate domain.

DPRK IT workers additionally falsify statement of work agreements, invoices, client communication documentation, and other documents for use with freelancing platforms, likely to satisfy know-your-customer and anti-money laundering (KYC/AML) measures or similar procedures that platforms have in place to ensure the legitimacy of user activity. These falsified documents may have minimal contact details to deter verification.

DPRK IT workers may also attempt to mask their nationality by representing themselves as South Korean or simply “Korean” citizens.

The advisory also provides some mitigation strategies and red flags to look out for.

Freelance work and payment platform companies should be aware of certain indicators that may denote the use of their platforms by North Korean IT workers.

Companies that employ freelance developers should also be aware of red flags, such as the use of digital payment services, especially ones linked to China. Inconsistencies in name spelling, nationality, claimed work location, contact information, educational history, work history, and other details across a developer’s freelance platform profiles, social media profiles, external portfolio websites, payment platform profiles, and assessed location and hours can also signal trouble. Remember the red flags Tenet Media chose to ignore, including strange time zones (Moscow) from which emails were sent by alleged “private investor” Eduard Grigoriann? And the spelling variations in his name erroneously sent in communications? Inconsistencies should be cause to investigate closer.

And if it looks like the developers are demanding payments in virtual currencies in an effort to evade KYC/AML measures and the use of the formal financial system, they probably are. If it walks like a duck…

Are the facilitators doing this intentionally?

Some US facilitators are witting, and some have their entire lives upended, their identities stolen, and their livelihoods compromised. Chapman was witting, and she was charged in April 2024 for her efforts to place overseas IT workers—posing as US citizens and residents—in remote positions at US companies. According to the Justice Department, Chapman defrauded more than 300 US companies using US payment platforms and online job site accounts, proxy computers located in the United States, and witting and unwitting US persons and entities.

Chapman and her co-conspirators committed fraud and stole the identities of US citizens to enable individuals based overseas to pose as domestic, remote IT workers, the Justice Department said.

A number of problems befall unwitting facilitators, who are victimized by having their identity stolen, according to the Wall Street Journal report. Typically, the North Koreans take the minimum amount of tax deductions, leaving the person whose identity they stole with a tax liability. Chapman’s laptop farm “created false tax liabilities for more than 35 U.S. persons,” prosecutors said in court documents.

Chapman pleaded guilty in February in the fraud scheme that generated $17 million for North Korea.

Monitor emerging methodologies.

Illicit actors change their methodologies quickly once their deceptions are discovered. Much like Russians who change the flags and registrations of their shadow fleet vessels as soon as a ship is sanctioned, North Korean IT workers adjust as well. For example, when employers figured out that asking an interviewee to wave their hand in front of their face during online interviews, causing AI software to glitch, was a good way detect North Korean generative AI tricks to alter their appearances, the North Koreans started hiring real tech-savvy individuals to ace the interviews.

If a worker you just hired all of a sudden asks you to send a laptop and other equipment to an address that’s different than the one on their employment records, you might want to examine the risk closer. Often the new remote worker will use an excuse such as a family emergency for the sudden change, so do your due diligence.

If the worker misses meetings or claims their camera isn’t working properly, be suspicious and be aware. I know a lot of us introverts hate using our cameras, but unless you know your interlocutor well, be very suspicious of those who insist on keeping their cameras turned off during calls.

Persistently lagging internet connection can also indicate trouble. We have all had slow connections during our careers, but if the problems persist and connections are unusually slow, you may want to look deeper, especially if this indicator is coupled with other red flags.

Background noise and efforts to obfuscate the remote worker’s background could be indications that the worker is actually working from a call center, rather than from the address they provided in the United States.

I have found that in most of the videos I’ve seen that feature AI-altered personas in an effort to trick an employer into hiring an illicit actor, the person looks drunk or high. Their eyes are half closed, and they seem to be moving or replying unusually slowly and lethargically. They refuse to put their hand in front of their face when asked, and will generally end the call when pressed. But deepfakes are evolving quickly, and firms must keep up.

In addition to this seemingly endless list of mitigation techniques, it’s a great idea to record the call, so experts can run a forensic analysis later—before offering a possible North Korean threat actor a job.