Recent reports and social media posts have spread a lot of misinformation about the government’s subscriptions to media outlets, including Politico, which is being accused of sucking up taxpayer dollars via USAID, misrepresenting subscriptions to news services as a “payoff” or as “funding” for media outlets.

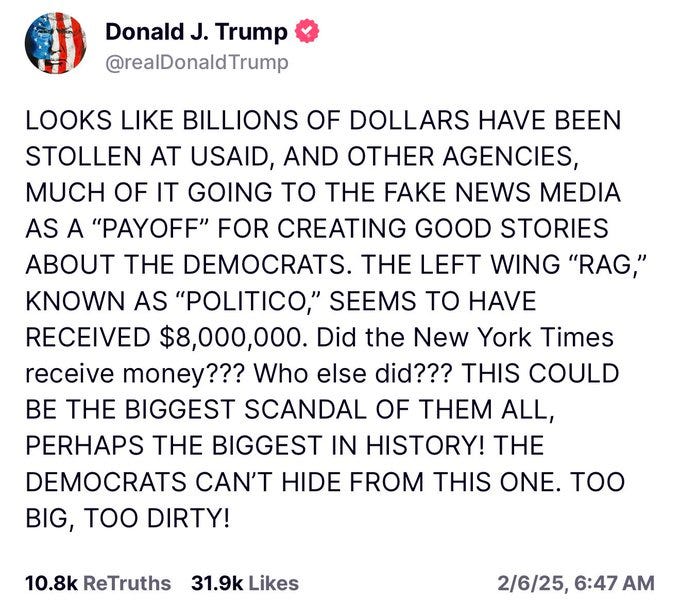

President Trump himself tweeted (or X’ed) a misleading accusation about about the “FAKE NEWS MEDIA” and USAID’s alleged “payoffs” for positive coverage.

Sigh.

My goal for this site is to steer clear of partisan politics, and discuss the issues that are driven by today’s political climate without regard to political parties or views.

So instead of pointing out the factual errors in this post, I’m going to talk about media subscriptions for government officials. Are they necessary? Are they important? What do government employees do with these subscriptions (other than keep informed about world events)? Do government subscriptions to Politico and other news outlets constitute “wasteful” spending?

Let’s discuss.

When I first entered government service, I raised my hand and took an oath.

The issues on which I worked were sensitive national security issues, and media reporting didn’t just help me do my job, but it was a critical part of it. The reporting is available to the public and is not classified, but in some cases, yes, you have to pay for it, like you do for Politico PRO. The subscription allows government officials to track policy, legislation, and regulations in real-time, providing news, intelligence, and other tools.

Sometimes media reports pointed me in the direction of possible issues I needed to research and assess. Sometimes media outlets were useful in corroborating other reporting. Sometimes, media reporting contradicted what I saw in classified reports, prompting me to dig deeper and do more research.

Media reports should not and were not the sole source of research, but they were a sign that a closer look at an issue was warranted.

Media outlets can be invaluable sources of information not only for analysis, but to prompt changes in policy.

Remember the International Consortium of Independent Journalists (ICIJ), whose research revealed that that Cyprus-based lawyers and accountants helped sanctioned Russian oligarchs avoid the seizure of their assets? In response to those revelations, Cyprus began working with the UK and the United States (FBI, specifically) to combat financial crime.

Foreign Policy in September 2023 reported that Greek shipping companies were selling ageing vessels to Russia, helping Moscow evade sanctions, and the Wall Street Journal that year reported that Greek shipping company TMS Tankers transported tens of millions of barrels of Russian crude and fuel since Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine began. In response to continued media attention, three major Greek shipping companies, including TMS, have stopped moving Russian oil from Europe to other continents.

Those two media outlets cost money, and the reporting they provide is well worth it.

At Treasury, I had access to various media outlets, from the Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and New York Times, to the Economist, Financial Times, and others. Every single newspaper and magazine provided critical insights into the issues we were analyzing.

Check Your Sources

Were newspapers, media outlets, and magazines the only sources we used in our assessments? Absolutely not! And each report had to be carefully assessed for possible biases and credibility.

Who owns the media outlet? Was it owned by the Internet Research Agency? Did it have links to the (maybe) late sanctioned Russian warlord Evgeniy Prigozhin? Is anyone with links to, for example, a Russian government official involved in the outlet?

Has it reported credibly in the past? Fake “news” websites have received a lot of attention during the past several years. These “sleeper” sites are a lot like shelf companies—shell companies that were created years ago and sat on the shelf to give the impression of longevity. In this case, the “news” outlets were created years ago and sat dormant until it was time to spread disinformation. Some of them started out gradually posting real, local news stories, and graduated to accusations about Zelensky’s mansion purchases. Check the history of reporting.

Who are the journalists writing these stories? In September, I wrote about Russian disinformation aimed at EU elections. A traitor (colloquial, not legal) named John Mark Dougan, a former Florida sheriff’s deputy who escaped to Russia in 2016 and was claiming to be an independent pro-Russian journalist in Donbass, created the DC Weekly website and claimed that a journalist named Jessica Devlin had joined DC Weekly as a “Senior Political Correspondent.”

Except she did not.

Last year, I cited Clemson University research about Devlin.

Jessica Devlin’s lengthy biography describes her as a “distinguished and highly acclaimed journalist whose career has taken her to some of the most critical and challenging regions of the world.” An extensive search found no record of Jessica Devlin’s acclaim, however, or, indeed, a record of any journalist by that name outside of DC Weekly. Her profile image is, in fact, a headshot belonging to Judy Batalion, a genuinely acclaimed writer in her own right and author of a New York Time’s best-selling novel.

What kind of language does it use in its reporting? A media source that uses words meant to evoke emotions, such as “horrifying,” “terrible,” “glowing,” and others generally tells me that the report is to be taken with a grain of salt and corroboration is needed.

Has the media outlet had to issue numerous retractions about its reporting? Does it have a reputation for accuracy? Could there be another motive for publishing the story?

Media reports can be crucial

We used US media, we read foreign news sources—sometimes in the local language and sometimes translated—we examined speeches of foreign politicians and analyzed foreign media reporting about our own government officials to glean how foreign counterparts perceived our people.

When conducting due diligence and assessing sanctions evasion methodologies (we did the latter a lot) we examined reporting about “shadow SDNs.” These are entities that may not explicitly appear on OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals List, but still may be considered sanctioned by force of law because they are 50 percent or more owned by a designated individual.

About a year ago, a Russian media outlet located in Riga, Latvia, did a fantastic report about a Russian military intelligence (GRU) officer, Viktor Labin, whose company, Belgium-based Groupe d’Investissement Financier, had been routing EU technologies that Russia needs to conduct its war in Ukraine through a shell company in Turkey to Moscow-based OOO Sonatek, owned by Labin’s son Ruslan. The media outlet, The Insider, published its first report linking Sonatek to Russian defense companies in October 2022, indicating that the company imported high-precision machine tools from European companies, several of whom distanced themselves from Sonatek after the first report was released.

The company, Labin, and his sons and procurement network were sanctioned by OFAC in May 2024. Was the Insider’s report the only source used as evidence for the designation? I doubt it. But was it a vital source of corroborating information? If I had to bet, I’d wager body parts that it was.

Government agencies ordered to cancel subscriptions

The first thing I would do every morning when I got to work is read the news.

What was going on in the world?

How were media outlets reporting on events?

What events were being covered?

Why were they covered, and what does other reporting reveal about the coverage?

Now, this is no longer being done. The Trump administration has ordered the federal government to end all paid news subscriptions for employees and agency offices across the executive branch.

A Trump administration official wrote the following in the email: “Pull all contracts for Politico, BBC, E&E (Politico sub) and Bloomberg. Pull all media contracts for just GSA – cancel every single media contract today for GSA only.”

The GSA is responsible for the federal government’s services relating to procurement, technology, and real estate.

This doesn’t just impact the intelligence community. Other departments, such as State, are canceling newspaper and media subscriptions worldwide. Diplomatic security, responsible for media monitoring, can’t monitor media if it doesn’t have its subscriptions. Ambassadors and other officials at posts worldwide can’t subscribe to local newspapers and keep informed about events that may be crucial to the United States.

How do we expect to have informed diplomatic security and other State Department officers if they cannot have their subscriptions to media reporting? Are they expected to pay for those themselves? Are they expected to read only free domestic reporting from Breitbart and OANN?

Even if they believe every word written by pro-administration media, are they not supposed to read other reporting as part of their job?

To be sure, this is not a First Amendment issue. Congress has not passed any law abridging the freedom of the press. But it is a severing of critical reporting that US government officials across the globe rely on to track legislation, monitor foreign issues that may not be covered by domestic press, and understand dis- and misinformation campaigns that have become a significant part of operations that influence elections and policy worldwide.

This is about keeping government officials, security officers, intelligence officers, and others informed.

Yes, they can surely buy subscriptions themselves.

Yes, they can sometimes access reporting free on the Internet.

But there are events that happen in real time that they could miss or simply be misinformed about if they only access free reports or media outlets friendly to one side of a political issue.

As intelligence officers, we should have tools that help us provide the best, most complete, most objective analysis possible to policymakers. Without having subscriptions to various media, that will be difficult to do.