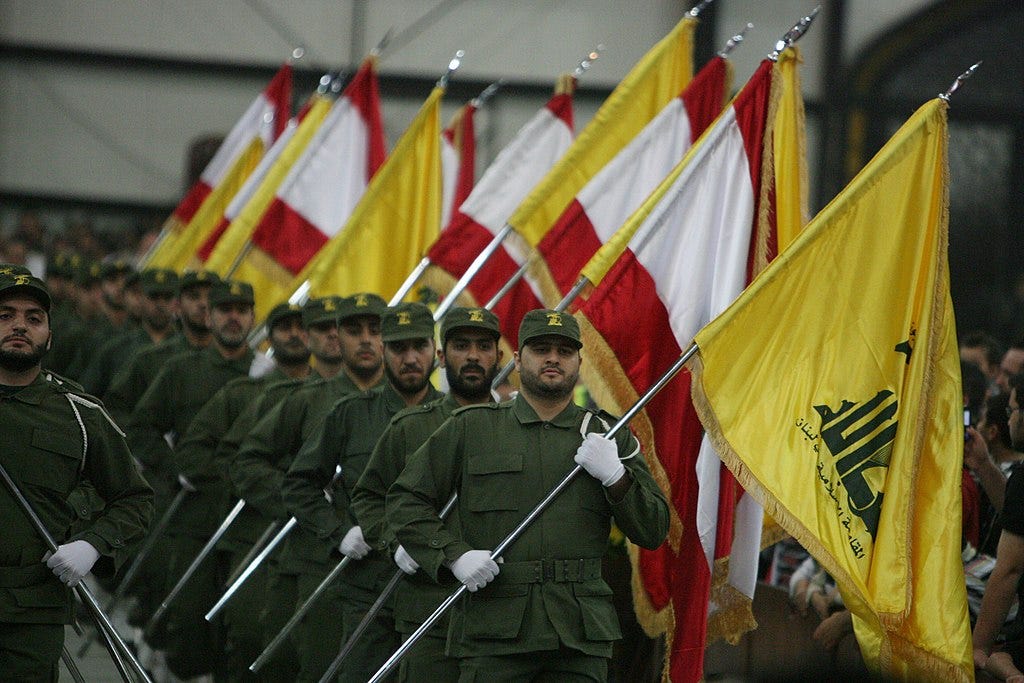

The Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) his week issued an alert to help financial institutions identify and report suspicious activity that supports US-designated foreign terrorist organization Hizballah. This is not the agency’s first alert on the issue. FinCEN in May released an advisory on Iran-backed terrorist organizations.

The current alert offers a comprehensive overview of Hizballah’s global criminal financial networks.

Why issue an additional alert? Because Hizballah has been wreaking havoc in the Middle East, and it needs resources. Lots of resources. It gets many of them from Iran and uses numerous methodologies to continue moving money.

Illicit activities generate millions for Hizballah. They’re involved in everything from drug trafficking to trade-based money laundering. They get funds from supporters worldwide and use shell and front companies to move funds. Other means of raising money include smuggling, taxation and extortion, and global investments. The formal financial system has also been used to move money for the Hizballah terrorists.

If you want to read more about Hizballah finances, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies wrote a comprehensive financial assessment on Hizballah in 2017.

…Hezbollah can launder money globally, through intricate networks built not just on religious and party allegiance, but also on blood ties and clan loyalties. Through their businesses, friendly Lebanese merchants support TBML schemes that move merchandise such as used cars, electronics, brand clothing, and cosmetics to cover the transfer of illicit proceeds. Hezbollah relies on money exchange houses, both in Lebanon and overseas, to move currency. It also has access to Lebanon’s banking system through a Hezbollah-controlled phantom bank, the U.S.-sanctioned Al Qard Al Hassan.

Treasury for years has been working to help financial institutions detect and deter financial transactions linked to Hizballah. The current alert is part of a larger effort, and it lists some indicators financial institutions must monitor and risky transactions they should identify when performing ehnanced due diligence.

Hizballah commits crimes worldwide in all sorts of ways.

When Hizballah smuggles energy products for Tehran, it generally uses vessels that are owned by front companies in third-country jurisdictions that sail under flags of convenience from unrelated third countries. In some cases, Iranian oil is blended with oil from other countries to further obscure its origins.

In addition, Hizballah uses deceptive shipping practices, such as falsifying documents, conducting ship-to-ship transfers at sea to further obfuscate the oil’s origin, disabling shipboard automatic identification systems, and changing the names of sanctioned vessels, to disguise their oil and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) shipments.

Smuggling of gold, electronics, and even drugs and cigarettes also generates funds for Hizballah. The goods and currency are either smuggled across borders or sold through front companies. The proceeds are either returned to Iran directly—usually via bulk cash smuggling—or laundered through the use of front companies.

The New York Times last year reported the case of Lebanese art collector, Nazem Ahmad, who was identified by US authorities as a Hizballah financier who has used an art gallery in Beirut, Lebanon, and an extensive personal collection that included high-end artiests to shelter and launder money. An indictment against Ahmad was unsealed in April 2023. According to the Justice Department, Ahmad and his co-conspirators used a complex web of business entities to obtain valuable artwork from US artists and art galleries and secure US-based diamond-grading services. And because Ahmad was sanctioned by OFAC in 2019, his involvement in the transactions had to be obscured. DOJ assessed that “[a]pproximately $160 million worth of artwork and diamond-grading services were transacted through the U.S. financial system.”

OFAC in April 2019 designated Belgium-based Wael Bazzi for acting for or on behalf of his father, US-designated Hizballah financier, Mohammad Bazzi. The elder Bazzi in September pleaded guilty conspiracy to conduct and cause US persons to conduct unlawful transactions with a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (i.e. Hizballah). Wael Bazzi, according to OFAC, has helped his father and a Lebanon-based associate facilitate payments for a business contract. The younger Bazzi likely established an account for Voltra Transcor Energy, in connection with Mohammad Bazzi’s attempted use of an intermediary company to move money to GTG and evade OFAC sanctions.

Treasury in June 2015 sanctioned a network of front companies, including the Car Care Center—a front company based in Lebanon that supports Hizballah’s transportation needs—and Al-Inmaa Group for Tourism Works and its subsidiaries that support Hizballah.

Red Flags

There’s no shortage of methodologies Hizballah uses to move assets, so what must financial institutions watch for and understand? FinCEN has provided seven different red flags that might indicate the transaction is linked to Hizballah.

If a party or counterparty has an obvious connection to Hizballah or is sanctioned by OFAC for affiliation with the terrorist group, financial institutions may want to take a closer look. Examine email and physical addresses, phone numbers, passport numbers and virtual currency addresses. Any number of tools exist to help with that.

If a customer or counterparty uses a foreign financial institution identified as being of “primary money laundering concern” under section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act—especially for links to Hizballah—that’s a major red flag and a suspicious activity report should be filed. Here’s looking at you, al-Huda Bank!

If a customer conducts transactions with a financial institution—including one that offers services in digital assets—that operates in a high-risk jurisdictions for Hizballah terrorist financing activity (think: the tri-border area (TBA) of South America between Brazil Argentina, and Paraguay, the Middle East, or West Africa, that’s a red flag. Worse yet, if the entity involved and has opaque ownership or beneficial owners associated with Hizballah, that’s an indicator to stay away.

The use of front or shell companies whose beneficial ownership information indicates that they may have a nexus with Hizballah is a no-no. Companies that list residential addresses or that are colocated with other companies are indicators of shell or front companies. If they’re located in a jurisdiction at high risk of Hizballah activities, you’d be wise to stay away.

Although the majority of trade in recent years has been open account trade—trade that doesn’t demand payment up front—and therefore, financial institutions have little documentation to examine, when they do have shipping documents or invoices, those can be a treasure trove of information. Invoices—particularly for shipments of electronics leaving the United States for the TBA or China, or used cars being shipped from the United States to West Africa—and that appear to over- or under-charge the recipient should be viewed as suspicious. If the goods listed in documentation do not appear to correspond with the counterparty’s stated line of business and/or if the payments for those goods are facilitated by a Lebanese or Hizballah-connected financial firm located abroad, caution should be used.

Given our discussion about Hizballah’s involvement in illicit energy shipments from Iran, transactions and wire transfers that refer to underlying commercial activity that involves bills of lading with no consignees or involves vessels that have been previously linked to suspicious financial activities or registered to sanctioned entities connected with Hizballah, the Huthis, Iran’s IRGC-QF, or the Syrian regime should be indicators that further examination is warranted. Financial institutions also know what fraudulent documentation looks like, so they need to watch for that as well, especially if the documentation lacks key information.

And then, there are your risky business sectors. Customers engaged in the real estate, import/export, construction, diamonds and precious stones, or high-value art sectors with numerous international counterparties in high-risk jurisdictions for Hizballah financing should be treated as high-risk. If they make an unusually high number of cash deposits in business accounts, transfer funds from business to personal accounts or vice versa, or use personal accounts or personal credit cards to make business payments, extra scrutiny may be warranted.

Each financial institution’s risk appetite is different, and banks doing business in high-risk jurisdictions for Hizballah activity will probably encounter these red flags often.

The alert is a guide, and although financial institutions that transact in geographies at high-risk for Hizballah activity aren’t required to close down in those jurisdictions, they do need to up their compliance game, perform enhanced due diligence, and watch closely for signs of illicit activities. Otherwise, I can’t imagine how they can keep their correspondent accounts with global banks and their access to the global financial system.

FinCEN's alert is all well and good, but with do nothing to stop the Hawala money moving around, and that is a significant amount that is pretty much untraceable.