I will admit that part of my libertarian (small “l”) heart had doubts about the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) - the bipartisan transparency law aimed at curbing money laundering and tax fraud. Why does the government need to know who owns what? Is there an assumption that a person who owns an LLC is a criminal? Why expend resources on digging up beneficial ownership? Why impose onerous, burdensome requirements on US business owners, as Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently said?

But then, the illicit finance geek in me kicked in.

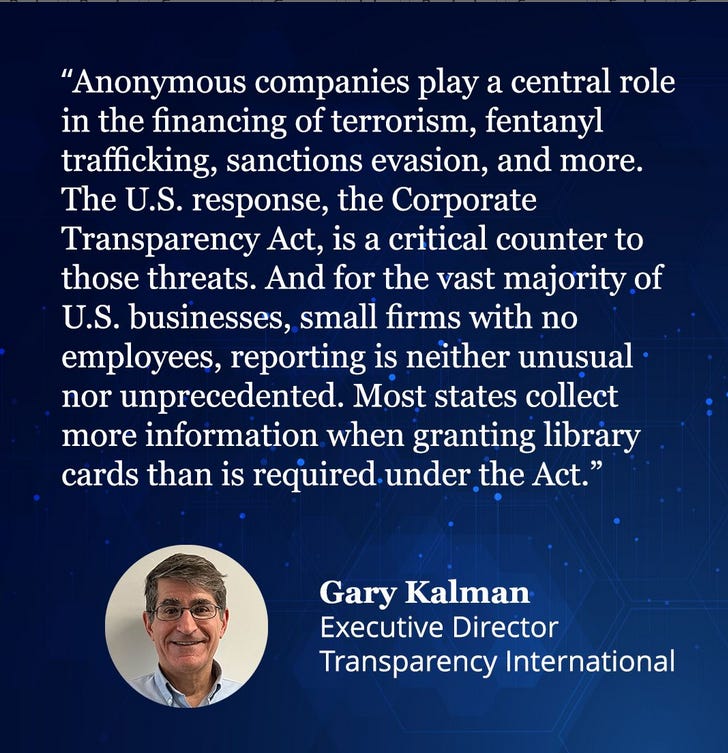

Anonymous shell companies are the ultimate tool to hide and move dirty assets, evade sanctions, and store misappropriated funds, according to Transparency International. They are used to obscure assets in 85 percent of cases analyzed by TI.

Are these requirements really as onerous as Bessent makes them out to be? I went to FinCEN’s website, and registered an LLC - all but actually submitting the information. It took me less than 10 minutes.

The information required is simple—less than what you have to provide to purchase real estate, open a bank account, or buy a car.

Reporting companies must provide (1) their full legal name, (2) date of birth, (3) residential address, and (4) a unique identifying number and issuing jurisdiction from an acceptable identification document. Scan your ID and you’re done.

It’s not burdensome. Many have argued that it’s barely sufficient. But it was a start.

Until recently.

No more enforcement

The Trump administration this month decided that the U.S. Treasury will “not enforce any penalties or fines associated with the beneficial ownership information reporting rule under the existing regulatory deadlines, but it will further not enforce any penalties or fines against U.S. citizens or domestic reporting companies or their beneficial owners after the forthcoming rule changes take effect either. The Treasury Department will further be issuing a proposed rulemaking that will narrow the scope of the rule to foreign reporting companies only.”

This decision is couched as an effort to reduce the burden on US business owners, but the burden is minor and the threat is very real. There is a national security angle to this, according to the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

In 2017, for example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) revealed that at least 26 U.S. government agencies leased commercial real estate from foreign-owned companies, some of which was used “for classified operations and to store law enforcement evidence and sensitive data.” The GAO further noted that it “was unable to identify ownership information for about one-third of [the government’s] 1,406 high-security leases as of March 2016 because ownership information was not readily available for all buildings.”

Congress in December 2020 passed the Secure Federal Leases from Espionage And Suspicious Entanglements Act, which requires federal government agencies to identify the beneficial ownership of any building in which it leases space and report whether the building is owned by any foreign parties. But what if these foreign parties are legal permanent residents of the United States?

The full testimony is here.

Many of the illicit actors involved in establishing shell companies in the United States are acting on behalf of sanctioned oligarchs, kleptocrats, and other thieves. They are a threat, and Treasury will not enforce the CTA in these cases, because they technically are not foreign. These guys are not “foreign”:

Da Ying (David) Sze, who coordinated a $653 million money laundering conspiracy, operated an unlicensed money transmitting business, and bribed bank employees in connection with financial transactions on behalf of drug traffickers—the very ones the current administration claims to be targeting—is a Queens, NY resident.

Olga Shriki, who tried to launder money for sanctioned Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska through shell companies is a naturalized US citizen.

A US citizen, Jack Hanick, worked with sanctioned Russian oligarch and nutty Putin acolyte Konstantin Malofeyev to illegally transfer a $10 million shell-company investment that Malofeyev had made in a US bank to a business associate in Greece, in violation of US sanctions.

The CTA had bipartisan support

In a statement before the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee in 2019, Acting Deputy Assistant Director, of the FBI’s Criminal Investigative Division, Steven M. D’Antuono raised the alarm about anonymous shell companies being used by illicit actors and how beneficial ownership could help law enforcement track these ctiminals.

The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crimes estimates that global illicit proceeds total more than $2 trillion annually, and proceeds of crime generated in the United States were estimated to total approximately $300 billion in 2010. For an illegal enterprise to succeed, criminals must be able to hide, move, and access these illicit proceeds—often resorting to money laundering and increasingly utilizing the anonymity of shell and front companies to obscure the true beneficial ownership of an entity.

The pervasive use of shell companies, front companies, nominees, or other means to conceal the true beneficial owners of assets is a significant loophole in this country’s anti-money laundering (AML) regime. Under our existing regime, corporate structures are formed pursuant to state-level registration requirements, and while states require varying levels of information on the officers, directors, and managers, none require information regarding the identity of individuals who ultimately own or control legal entities upon formation of these entities.

The passage of the Corporate Transparency Act was seen as a great step toward transparency and accountability, even by the first Trump administration.

Now, the new Trump administration has taken a gigantic step backwards, especially with its plan to allow wealthy foreigners, including Russian oligarchs, to buy citizenship in the United States for a mere $5 million.

And guess what!

Once they buy themselves that golden passport, they will no longer have to declare beneficial ownership either, according to the Treasury announcement. The Corporate Transparency Act—a law passed by Congress and signed by the President—will not be enforced, allowing anyone who pays the $5 million to establish anonymous shell companies in the United States and potentially hide misappropriated assets and other dirty money.

Are we a nation of laws, or aren’t we?

Foreign kleptocrats and other actors inside our borders

Nigerian politicians accused of misappropriating assets in their country have family and corporate links to properties worth millions of dollars in the Carolinas. Notable Nigerian public officials who bought land in the Carolinas include Orji Uzor Kalu, a former governor of the oil rich state of Abia and a current Nigerian senator, according to recent research. Kalu is linked to five properties in South Carolina worth at least $2 million and properties worth more than $4.7 million in the Charlotte metro area. He also owns two properties outside Washington, DC, including one home—worth roughly $2.5 million—with eight bathrooms and a tennis court.

The CTA also contained requirements that real estate professionals identify the true buyers of properties. But Treasury will not enforce the law.

My friend Debbie LaPrevotte, a retired FBI agent, highlights that efforts to weaken anticorruption laws have far-reaching impacts in the United States and abroad.

In the U.S., large influxes of dirty money distort American real estate markets, hiking real estate prices for everyone. It facilitates corruption in low-income countries, often leading to more political oppression and violence.

Cartels use anonymous shell companies in the United States to move and hide proceeds of illicit fentanyl and other drugs. This is supposed to be a priority for the current administration, but there seems to be no interest in enforcing the law.

Politically exposed persons (PEPs) and their facilitators also use anonymous financial vehicles in the United States to launder money, according to a FinCEN Advisory in 2018.

PEP facilitators commonly use shell companies to obfuscate ownership and mask the true source of the proceeds of corruption. Shell companies are typically non-publicly traded corporations or limited liability companies (LLCs) that have no physical presence beyond a mailing address and generate little to no independent economic value. Shell companies often are formed by individuals and businesses for legitimate purposes, such as to hold stock or assets of another business entity or to facilitate domestic and international currency trades, asset transfers, and corporate mergers.

If these facilitators are legal permanent residents or US citizens, Treasury won’t bat an eyelash at their refusal to take 10 minutes out of their day to complete beneficial ownership paperwork. So will they bother? Probably not.

When I was on assignment from Treasury to SOUTHCOM several years ago, one of my coworkers who had moved to the Miami area from Washington DC had trouble finding a house. He and his wife couldn’t purchase a home, because the moment they tried to put a contract on a house, an anonymous LLC registered somewhere in the United States would swoop in, buy the home for twice or three times its selling price, and pay cash. They remained in an apartment for several years before finally being able to buy a house.

And then there’s the trust

I’ve railed against FATF for not including Russia on at the very least its grey list of countries under increased monitoring. FATF’s entire mission is to be a global illicit finance watchdog, and by not including Russia on its grey list of countries with weak illicit finance regime, despite overwhelming evidence that the country is engaged in violations of sanctions and other illicit financial transactions with malign actors, such as North Korea, I argued that FATF abdicated its responsibility.

As a member of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the United States has a concrete foreign policy obligation to collect critical beneficial ownership information to mitigate the risks of money laundering and terror financing, according to the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

FATF explains that tough beneficial ownership standards “will help prevent the organised criminal gangs, the corrupt and sanctions evaders from using anonymous shell companies and other businesses to hide their dirty money and illicit activities.”

But not if anticorruption and transparency laws aren’t enforced.

Trust in the US financial system—its strength, its stability, its transparency, and its integrity, so to speak—is part of the reason why the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency. It’s a so-called “safe haven” currency to turn to in times of economic crisis.

Foreign investors often refuse to put their money in developing countries where corruption can run rampant. What will happen to the United States if corruption is perceived to be on the rise, laws are arbitrarily not enforced, and illicit actors can exploit the financial system with impunity?

Transparency International has already dropped the United States by four points on its Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for last year compared with 2023. The CPI is one widely used metric to determine a nation’s corruption, and a number of investors and other countries use it as part of their toolbox to determine where to park assets.

The other popular metric is the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, which describe broad patterns in perceptions of the quality of governance across countries and over time.

How much longer will the United States be a “safe haven” if it’s to be perceived as a haven for corrupt actors?

How much more will the United States drop, and how will perceptions of the integrity of our financial system change after our refusal to enforce our own laws?

Likewise, US corporations playing fast and loose with foreign actors is nothing new. Before US entry into WW2, Texaco was notorious for multiple violations of the Neutrality Act by smuggling oil past the British blockades to sell it to the Nazis.